What's In Your Board?

A Project of Sustainable Surf and the Surfing Heritage and Culture Center

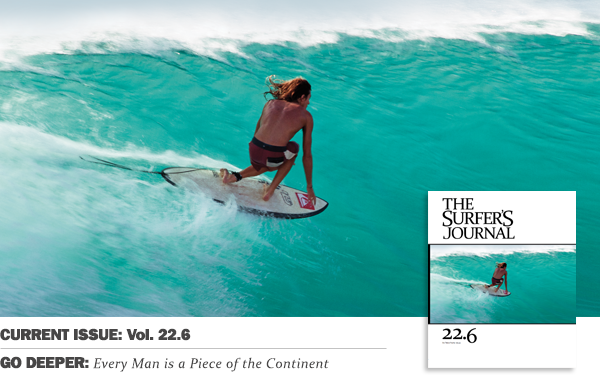

The Surfer’s Journal article: Toward Conscious Surfing

Toward Conscious Surfing.

If less toxic surfboards have improved in quality and availability, why aren’t more surfers riding them?

By Todd Woody

For half a century we’ve been riding the same surfboard. Design and performance have made quantum leaps over the decades but the typical surfboard remains a chunk of toxic polyurethane slathered with toxic polyester resin. It’s bad for the sea life and bad for shapers and surfers who play in an increasingly carbon-polluted ocean. The sudden closure of Clark Foam in 2005 was supposed to liberate the surboard from its Gidget-era time warp, unleashing new technologies and materials that would spawn a more environmentally friendly, more sustainable board.

It hasn’t quite worked out that way. Nearly a decade later, polyurethane boards still dominate sales and so-called “green” surfboards remain at best a very small niche market. “I have four boards on order right now and I would love to have an environmentally sustainable surfboard but the option was never given to me,” says Scott Bass, chief executive of The Boardroom, a tradeshow for shapers.

Change is afoot though. After years of false starts and failed experiments, the industry has begun to coalesce around a certified standard for sustainable surfboards that don’t compromise performance or require significant changes in manufacturing. Large surfboard companies like Channel Islands and Firewire, meanwhile, have begun to sell “Ecoboards”—albeit in small numbers. But as I discovered, finding these boards requires some searching and conscious effort.

When Clark Foam shut its doors, it opened up the market for EPS/epoxy boards. By definition, those boards were less environmentally harmful as polystyrene is more durable than polyurethane and does not contain carcinogens. Additionally, epoxy resins do not emit volatile organic compounds or require the use of toxic solvents. It was an improvement but hardly sustainable.

Then came attempts to make soy-based foam, which resulted in heavy, brown blanks—hard to shape and worse to ride. “It had the right ethos but the materials weren’t on par with what a high-performance board demands,” says Michael Stewart, co-founder of Sustainable Surf, the non- profit that created the Ecoboard standards for sustainable surfboards.

In 2009, a startup called Green Foam Blanks began selling recycled polyurethane to shapers in San Clemente’s surf ghetto. Upon customer request, Lost’s Matt Biolos and other shapers would make a Green Foam board. Yet shapers were not exactly pushing the product. “I would use them if the customers wanted one,” Jerry O’Keefe of Soul Stix told me in 2011. “But I don’t think they got it where it’s superlight and super strong, so it’s not being widely used.”

O’Keefe was voicing a common sentiment: environ-mentally superior surfboards offer inferior performance. “Surfers are not going to sacrifice the performance of a light board for being green,” Biolos told me in 2009.

Stewart and partner Kevin Whilden started Sustainable Surf to overcome such perceptions by awarding high-performance, green surfboards an Ecoboard seal of approval, much like the organic label for food. To qualify, a surfboard must be made from at least 40-percent recycled foam or 40-percent biological content such as wood. The resin must also contain at least 15-percent biological content.

That’s a somewhat low bar but one designed to get as many shapers involved as possible. It serves as a floor rather than a ceiling for sustainable surfboards. (Marko Foam, for instance, makes a 60-percent recycled EPS blank.) “We’re not saying these are 100-percent sustainable materials but that they’re more sustainable materials,” notes Stewart, a 44-year-old surfer with a background in sustainable product design.

“ What I would like to see actually happen is some- thing close to the ethos of the original surfboard,” he says. “That was a wood plank and if you lost that board it would wash up and someone else would find it and be stoked and go surf it. At the very least they biodegrade.”

“We are getting closer, step by step, to recapturing those materials,” he adds.

On the Channel Islands website, customers can already order any of the designs offered as an Ecoboard by selecting recycled EPS foam, bio-resin, and a bamboo deck. “This ain’t Gramp’s old ‘eco’ board—heavy, yellow, and low performance,” the site declares somewhat self-defensively.

Firewire, meanwhile, began making a new line of high-performance, wood-skinned Ecoboards called Timbertek this year. The company has also switched to bio-resins for all its boards. “At some point in the future, sustainability will become one of the driving product attributes needed to succeed in the market,” says chief executive Mark Price.

That’s because it’s not just do-gooders pushing that change. Pending California regulations could result in restrictions on chemicals like styrene used in polyurethane board making. “Ultimately the greatest thing would be if the industry could use the Sustainable Surf certification to comply with the new regulations,” says Cordon Baesel, a San Diego surfer and environmental attorney.

But will individual shapers and the sponsored surfers who ride their boards, and influence legions of buyers, embrace Ecoboards? While Stewart has put an Ecoboard in the hands of Torrey Meister, and Firewire has made Timberteks for team riders Michel Bourez, Sally Fitzgibbons, and Filipe Toledo, none are riding them in competition yet.

“They are so particular about their boards,” says Price. “They’re also loath to ‘experiment’ during the season. I don’t expect anyone to ride one this year, but there is a good chance for 2014 once we build them a quiver of Timbertek boards.” Price also acknowledges that Ecoboards remain a niche play. “Performance, price, and brand are still all ahead of environmental attributes,” he says. “I don’t think the consumer is willing to pay surcharge for eco credentials.”

I’m not so sure about that. The portrayal of surfers in media hasn’t changed much over the decades—young, male, and obsessed with speed. But paddle into the lineup and it’s a more diverse story—far more women, and parents surfing with their kids.

A 2011 study found that the typical surfer in the U.S. is 34 years old, college educated, and has an income of $75,000. Which is to say that you’re more likely to meet surfers like Kirk Haney and Cynthia Krueger in the water.

Haney is chief executive of SG Biofuels, a San Diego startup. He grew up in the Northern California town of Salinas, where he surfed cold, Central Coast breaks. “Would I pay more for an Ecoboard? Absolutely. But you got to get the surf shops to sell them,” says Haney. He pauses. “It’s got to perform, though. When I’m on a shortboard, I want to pretend I’m 19 even when I’m 41.”

At San Diego’s Ocean Beach, Krueger, a 47-year-old aerospace engineer surfs a Timbertek Spitfire. She had been in the market for a high-performance board when she stumbled across the Timbertek line on the Firewire website. “I probably would have paid a little more to have a more environmentally friendly board, but because it was exactly the same price as the other boards it was a no-brainer,” she says.

With some major manufacturers on-board and more surfers riding them, the environmentally sustainable board appears to be at a tipping point between noveltyitem and culturally accepted. “It’s an uphill battle as no one wants to roll the dice on their livelihood—whether it’s the competitive surfer or the shaper barely making ends meet,” says Bass. “It really comes down to showing that these boards are going to work for Kelly Slater and Dane Reynolds.”

A visit to two different surfboard makers shows how the sustainable future might unfold. A few blocks from Ocean Beach in San Francisco, Danny Hess shapes surfboards from salvaged redwood wine barrels, old walnut trees, and other reclaimed wood.

When Hess began building boards in 2005, he says most customers were far more interested in the aesthetics of his beautifully-crafted boards than their eco-cred. That’s changed. “Surfers are mature and educated and they’re searching for alternatives,” says Hess, who is 38. “When people come to order boards from me I explain to them that this is a salvaged redwood tail block.This is cork or poplar. And this is why I choose these materials, how they’re more sustainable, and make for a longer-lasting board.”

Such talk—and the $1,300 average price tags for Hess’s full wood boards—may invite Portlandia-like derision. Yet judging by his sales, he’s tapping a growing market, and his boards can be bought off the rack in surf shops, exposing potential buyers to an alternative to polyurethane.

But making these types of boards a larger phenomenon depends more on manufacturers like Firewire— which is incorporating sustainable materials into all its high-performance boards—and Stretch, which switched to EPS/epoxy construction after the fall of Clark Foam. When I drop by Stretch’s Santa Cruz factory to talk with general manager Dave Aumentado about ordering a new board, his pitch is all about performance: finding the right board for how and where I surf. But when I ask whether I can get a board made with recycled foam, bio-resin, a bamboo stringer, and recycled fins, he doesn’t blink. “Yeah, pretty much any of the green stuff you want to do, we can do it.”

Aumentado has learned through the years that sustainability sells best when it’s just part of the package. “We’ve been doing things this way for so long that for most of our customers the green thing is just an added bonus,” he says.

For Stewart, that points the day when a sustainable surfboard is just a surfboard. “That’s what happens in a real market transformation,” he says. “It’s not like this is cool and green—it’s actually better.